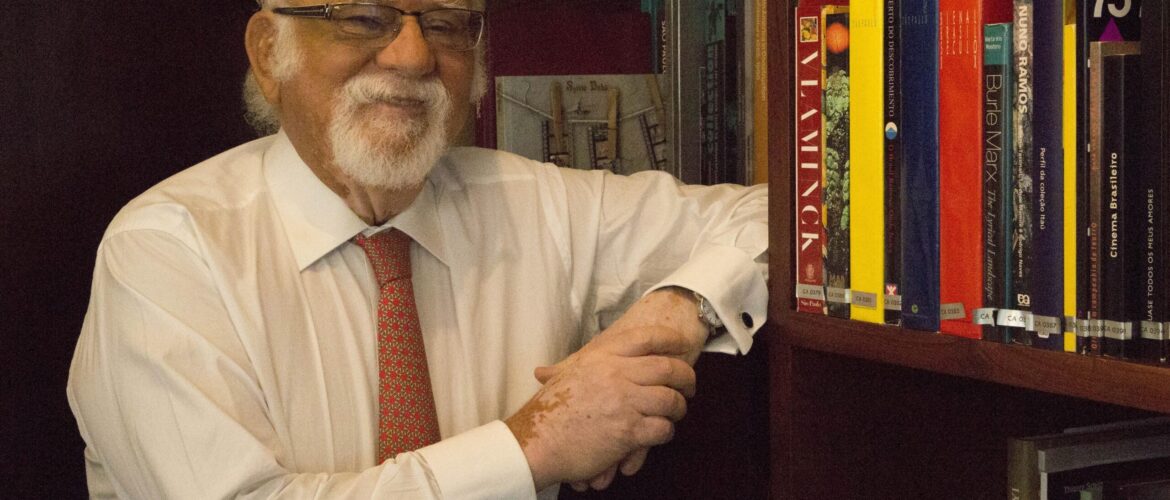

Interview with Danilo Santos de Miranda, Regional Director of Sesc São Paulo

About yourself

What is your professional background? And how did you end up working in the leisure field?

I studied sociology and philosophy. My professional career started in human resources and then I went on to work for an institution similar to Sesc, known as SENAC. By then, I was already familiar with the work done by Sesc and identified with it. Ever since its inception, in 1946, Sesc’s efforts have been geared towards the cultural development of its primary audience – professionals working in businesses and services, and that of the community, and it has always done so by offering leisure and cultural activities that are imbued with the spirit of education and transformation. It was my background and my firm belief in the educational power of leisure that led me to accept the position of Director of Sesc São Paulo in 1984. Now, 33 years later, I see myself as a cultural manager who is still restless when it comes to leisure issues, especially those to do with the democratization of leisure. It is still with that prospect in mind that I go to work every day.

What do you do for your leisure?

I love watching soccer games on TV. I also go out about four nights a week – to the theatre, to listen to music, or to contemporary dance performances. I take walks outdoors, close to nature and, to me, going out with friends and travelling is essential. Nevertheless, in my view, leisure is something that goes beyond rest, or even fun. I always see such moments as an opportunity for personal fulfilment, a time to appropriate and acquire knowledge. I have an interest in historical literature, such as Leonardo Padura’s novels. Reading has been doing me a world of good lately…

Is there any leisure experience in your lifetime that you particularly remember? Why?

Yes, absolutely. Always. I used to take part in bike rides a good many years ago. I have always attended concerts at Sesc Pompeia, even before I joined the institution. I often went to the movies around Paulista Avenue, which is considered to be the financial epicentre of the city and an area where a large part of cultural venues are concentrated. I have seen the city change over time, there has been an exponential increase in the number of cars on the streets, traffic jams… It is a rare thing to see someone casually riding a bicycle on the streets these days, as we used to. So, my affective memory often takes me back to how we appropriated the streets, public spaces… and now, it makes me happy when I see an effort towards increasing bike paths in the city, for instance, or turning Paulista Avenue into an open space for pedestrians, a place of leisure for all, on Sundays and bank holidays.

Did that leisure experience have any impact on you? If so, which one?

All good memories are eventually consolidated into something like a theory that you set for your life, your own individual theory, an ethics for yourself, a set of tastes and good things that allow life to be lived a little more lightly. Leisure is part of the most sublime that life can offer to help you understand the world. It is very important to have time for yourself, to explore what is relevant in life and to enjoy the experience.

Knowing a bit more about leisure around the world

Which do you think have been the main changes in terms of leisure in the last years in your nearest environment?

While the leisure issue has been part of academic and institutional debates since before the 1960s, Brazil’s track record in political construction has not been conducive to the acknowledgment that leisure is essential. Sesc played a pioneering role in that debate when it drew from references by Joffre Dumazedier, the French leisure expert who stressed the importance of free time and its educational quality. Only in 1988 was leisure guaranteed as a Social Right by the Brazilian Federal Constitution. From then on, I have noticed that people have become more aware, even if only slightly more so, but, still, more aware of their right to leisure, and some of them have been claiming that right to quality leisure more frequently. After experiencing a boom in the past decades, I feel that large cities have now been trying to reconnect with nature. The importance of having green spaces is an increasingly hot topic – which is of vital importance. Sesc São Paulo is about to open an RPPN – Reserva Particular de Patrimônio Natural (Private Natural Heritage Reserve) to the public, in a city called Bertioga, which is located on the coast, and will offer one of the first ever accessible trails for people with physical disabilities. Because it pervades so many issues, leisure can also be a vector for social and community development.

What would you say it is specific about leisure in your city, country or region, with regard to other parts of the world?

Working in the Leisure field in São Paulo is very challenging. We are talking about a Megacity, with over 12 million people (and that doesn’t include the 8 million living in the surrounding cities that make up the Greater São Paulo Area), that is anything but obvious to those who live there, or visit it. We sometimes have to deal with paradoxical situations, such as skyscrapers and a dirt soccer field in the middle of a public square sharing the same district – the city’s financial epicentre. The city has a lot to offer and can cater to every taste, but distribution is still unequal. With that in mind, Sesc has been trying to encompass different areas of the city, as well as cities across the state, where there is an even bigger shortage of cultural facilities. Sesc manages 20 cultural and sports centers in the state capital alone. There are 17 others across the state (and the prospect of more opening over the next few years). On average, 400.000 people take part in Sesc‘s activities every week. These people are interested in experiencing or enjoying moments of leisure, concerts, dance performances, theatre plays, movies, visual art pieces, not to mention all the physical activities, different sports modalities, such as football, volleyball, basketball, swimming, tennis, judo, among others, and countless other options available.

Considerable focus has also been placed on social and environmental issues, either through educational initiatives, the park-centers, or the RPPN, as I mentioned earlier. Brazil is a massive country that boasts extraordinary cultural wealth, but, unfortunately, there is still very little encouragement when it comes to these manifestations. The diversity of music styles, dance and popular tradition is everywhere, and some of it still survives as a form of resistance. The city of São Paulo welcomes immigrants from all over the country and many parts of the globe. In point of fact, we have the largest Japanese community outside of Japan. There are refugees from Syria, Congo, Haiti… All these people bring their customs and culture with them, and those are then blended with ours… there is no doubt that this plurality enriches us.

By the way, how do you say leisure in your language?

Lazer.

About the future of leisure studies

What would you say is the main opportunity for leisure in the coming years? And the main challenge?

I believe the main opportunity lies in turning leisure time into a time for all-encompassing human development, a time to broaden horizons and to expand one’s view of the world. In fact, I think the opportunity lies in making this a global view of leisure, establishing international connections and creating links that can strengthen us as a society. I believe the biggest challenge is getting people, as well as governments, to understand that leisure is vital and much needed. It is never a banality. Making sure that leisure is never at the service of empty entertainment, never used merely as a means to spend time, but an investment of time. And ensuring that it is sustainable in every sense.

What skills and competences do you think professionals of leisure will need in the following years?

Professionals of leisure tend to be people with fresh ideas who are aware of the transformative power of leisure and of its importance to the advancement of individuals. They are educators in the broad sense of the word, that is, they mediate the educational process that takes place through leisure. I think professionals in this field are constantly challenged to exercise their creativity. Therefore, among the many necessary skills, two are essential in my view: they must be restless – that way their work will always bring an element of exploration and innovation to leisure, and they must be able to think judiciously, so as to avoid simply substantiating the entertainment market and to truly provide people with meaningful and transformative leisure experiences.

One of the challenges we face (and here I include Sesc and the WLO, as partners that operate in the same field) is to make this an increasingly more universal right, and preferably guaranteed by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

How do you think leisure studies will evolve in the coming years?

In my view, leisure studies have a major challenge ahead, especially considering the changes that the so-called “social times” have been going through. In the past, there used to be working time and non-working time, during which people would experience leisure. Now, it seems to me that the line between those two different times is progressively more blurred… Having diaries and e-mail available on smartphones, home-offices and the loosening of labour laws also have an impact on that. I think leisure studies become broader and deeper as progress moves forward. More and more people claim to have less time for themselves, to look after their own health through physical activity and healthy eating habits, or to spend with their families. As our work becomes more demanding, we get too busy doing and forget about being… Time seems to have become scarcer over the last few years… the time for being, for contemplating and living life, and not simply spending it in traffic, in endless meetings, on a mobile phone, tablet or TV…

Counteracting that trend is, to me, the biggest challenge leisure studies have to tackle. New technologies play an undeniable influential role as accelerators of social dynamics. Although their excessive use can hinder other essential activities – such as human interaction, they can also be exceptional tools for development.

About WLO expectations

How do you think WLO has helped you?

The WLO plays a major role in bringing institutions that share the same values together, its networking is highly relevant, and it offers the Centers of Excellence, in addition to concentrating professionals of leisure from five different continents. To be part of something like that is extremely important to an institution like Sesc, which plays such a major role in implementing initiatives and producing knowledge on leisure in Brazil. Not to mention that I was a member of the WLO Board when it was still known as WRLA. When we held the 5th World Leisure Congress, in 1998, Sesc was still taking its first steps towards organizing global conferences and the feedback on the Congress was very positive, both in Brazil and abroad. I am certain that all the professionals of leisure who were here left with a positive impression of who we are, what we believe in and how we go about accomplishing our mission to make good quality leisure more accessible to the population.

What do you think WLO should promote more? Is there anything specific you are missing?

We have been thinking that the WLO could increase its presence and contact network in Latin America, where leisure needs to be more encouraged by both public policies and private non-profit initiatives. There are many competent people generating knowledge and implementing successful leisure initiatives here. Language can be a barrier, so, perhaps investing in becoming a bilingual organization would be a huge step towards bringing Latin-American countries, researchers and institutions together. Maybe that will be easier now that the headquarters are in Bilbao.

How would you encourage people and institutions to collaborate and become WLO Members?

My advice would be to bring people closer so they can get to know the work that the WLO has been doing, especially in the last few years. I would highlight the new commissions program and the Centers of Excellence as the possibilities with the most potential to engage new members and encourage their participation.

About WL Congress 2018

WL Congress 2018 will take place 20 years after WL Congress 1998, also organised by Sesc in São Paulo. What do you think has been the impact of the 1998 WL Congress at Sesc in São Paulo?

The 1998 Congress was most certainly a milestone in the history of World Leisure Congresses, both in terms of the number of scholars who attended and the quality of the debates. The event took place at a time of severe social and economic crisis, and debating topics such as leisure and free time within that context was highly challenging. But, we did it – reflections revolved around two main themes: the effects of globalization and the qualitative aspect of what to do with one’s free time. Moreover, once the five days of the meeting came to an end, the São Paulo Declaration was composed: a definitive charter containing basic guidelines for official leisure policies, ratified by the UN and collectively endorsed by Congress participants. The São Paulo Declaration – Leisure in a Globalized Society was based on article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states that all cultures and societies must recognize the right to rest and to leisure.

What are your expectations with the organisation of the WL Congress 2018?

My expectations as the director of Sesc São Paulo are to bring together people from all continents and to enable as much experience sharing and knowledge dissemination as possible. I believe the WLO and Sesc will be able to consolidate the view that everyone has a right to leisure, and that it is of vital importance to the structuring of society. To raise awareness of the need to make it an increasingly more universal right. We cannot underestimate the quality of the leisure experiences we offer. Public spaces (or spaces of public interest, as is Sesc’s case) must be inviting and fully accessible for the enjoyment of leisure. We must strive to use technology increasingly in our favour and to knock down the barriers and prejudices that still prevent all people, without exception, from having access to diversified leisure experiences that can contribute to their development and to the enhancement of quality of life for all. Hence, I see this Congress as an opportunity to ensure the appreciation of leisure as a concept that is as important as the right to education, apart from anything else because leisure is also educational.